BY KIERAN LINDSEY, PhD

Ever notice how many of the colloquialisms we use for comparisons aren’t all that apropos, or even true? Like…

– graceful as a swan (have you ever seen one on land?)

– dull as ditchwater (believe me, that liquid is lively at the microbial level)

– happy as a clam (surely not all clams are cheerful, especially when yanked out of their bed for an impromptu dinner invitation)

So forgive me for making an obvious, if not completely accurate, correlation between North American softshell turtles and pancakes. True, these aquatic reptiles aren’t literally as round and flat as flapjacks… then again, not every flour-based breakfast food cooked on a griddle is invariably spherical and level.

My home town of St. Louis, Missouri, is home to two softshell species — the Eastern Spiny Softshell (Apalone spinifera), and the Midland Smooth Softshell (Apalone mutica). Both are members of the Apalone genus, both are aquatic, they’re circular in shape (or at least an oval), and both are more horizontal than vertical (although varying in size and thickness).

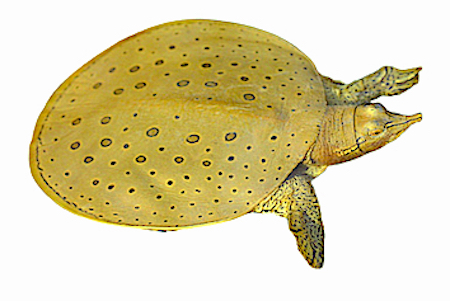

Six subspecies of spiny softshells pour across the central U.S. states, spread into Canada (Ontario and Quebec), and dribble into Mexico (Tamaulipas, Nuevo, León, Coahulla, and Chihuahua), yet these Midwesterners resemble the European style of round, thin unleavened hotcakes. Their common and scientific names refer to pointy cone-shaped knobs on the leading edge of the body’s rim. Juveniles and adult males are batter-yellow to olive-green and splattered with maple syrup brown spots, while females darken to mottled molasses as they age. Males widen to salad plate circumference of 5 to 9½ inches (13-24 cm), and you can double that to dinner or large charger plate (9½ to 19 inches or 24-48 cm) for the average size of a female spiny.

Six subspecies of spiny softshells pour across the central U.S. states, spread into Canada (Ontario and Quebec), and dribble into Mexico (Tamaulipas, Nuevo, León, Coahulla, and Chihuahua), yet these Midwesterners resemble the European style of round, thin unleavened hotcakes. Their common and scientific names refer to pointy cone-shaped knobs on the leading edge of the body’s rim. Juveniles and adult males are batter-yellow to olive-green and splattered with maple syrup brown spots, while females darken to mottled molasses as they age. Males widen to salad plate circumference of 5 to 9½ inches (13-24 cm), and you can double that to dinner or large charger plate (9½ to 19 inches or 24-48 cm) for the average size of a female spiny.

Two subspecies of smooth softshells are also indigenous to the central and south-central river basins of North America, although their range is constrained to the U.S., stretching from North Dakota south to Louisiana, New Mexico east to Tennessee. Both males and females have a somewhat fluffier figure befitting a blintz or some buttermilks. Males broaden to saucer size (5 to 7 inches or 13-18 cm in diameter), while females are twice again that expansive (7 to 14 inches or 18-35 cm). The two sexes differ in color as well – females tend to be beef stock brown or olive, males and juveniles tend toward olive-drab – but all are flecked with dark brown bits of random shapes and sizes.

Two subspecies of smooth softshells are also indigenous to the central and south-central river basins of North America, although their range is constrained to the U.S., stretching from North Dakota south to Louisiana, New Mexico east to Tennessee. Both males and females have a somewhat fluffier figure befitting a blintz or some buttermilks. Males broaden to saucer size (5 to 7 inches or 13-18 cm in diameter), while females are twice again that expansive (7 to 14 inches or 18-35 cm). The two sexes differ in color as well – females tend to be beef stock brown or olive, males and juveniles tend toward olive-drab – but all are flecked with dark brown bits of random shapes and sizes.

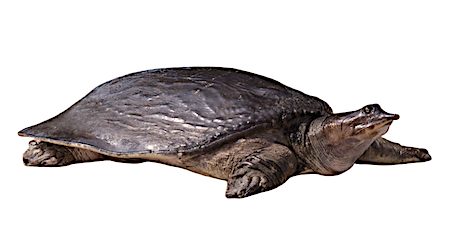

The Florida softshell (Apalone ferox) is native to four southeastern U.S. states – Alabama, Florida (no surprise there), Georgia, and South Carolina. In keeping with the region’s dietary reputation, this species is suitably supersized, more Belgian waffle than crêpe. Males measure up at 6 to 13 in (15-33 cm), and females are 3-5 times larger (11 to 25 inches or 28-63 cm). Juveniles have a cornmeal yellow margin on top and vary in hue from chartreuse to baguette tan to pretzel brown, with a plummy gray to blackened base. By adulthood, their exterior is wrinkled and oblong, and has faded to variegated walnut brown or caper green above, and parchment paper white below.

The Florida softshell (Apalone ferox) is native to four southeastern U.S. states – Alabama, Florida (no surprise there), Georgia, and South Carolina. In keeping with the region’s dietary reputation, this species is suitably supersized, more Belgian waffle than crêpe. Males measure up at 6 to 13 in (15-33 cm), and females are 3-5 times larger (11 to 25 inches or 28-63 cm). Juveniles have a cornmeal yellow margin on top and vary in hue from chartreuse to baguette tan to pretzel brown, with a plummy gray to blackened base. By adulthood, their exterior is wrinkled and oblong, and has faded to variegated walnut brown or caper green above, and parchment paper white below.

What all three of these turtles have in common, with each other and their fellow members of the Trionychidae family, is a preference for the life aquatic, and a pliable, al dente carapace instead of the rigid scales of, say, an Eastern box turtle. Not that a soft shell is required for a turtle to live submerged, as ably demonstrated by the red-eared slider. Even so, the silky smooth nappe of the Apalone trio provides a speed and agility advantage over the starchy domed croûte of their cumbersome kin — whether moving through water, along the muddy or sandy bottoms of rivers and lakes, or even on land.

Softshells also have an elongated neck. When extended, and affixed as it is to the disk-shaped carapace, one can’t help but be reminded of a skillet handle. The lengthy neck is an anatomical adaptation that allows these turtles to sink into a mud or sand substrate and yet continue to breath through their tubular, ziti-like nostrils while immersed in a foot or more of water, waiting for their next meal.

Stealth is not their only dinnertime strategy, though. Apalone turtles are speedy swimmers who will pursue prey. Smooth, spiny, and Florida species are all predominantly meat-eaters, subsisting on fish, frogs, mollusks, crustaceans, and other invertebrates, as well as birds and small mammals when they appear on the menu. They’ll also include an occasional side-dish of algae or aquatic vegetation.

You know, on second thought, maybe the food analogy I’ve been using throughout this post is rather insensitive because Homo sapiens have long considered softshell turtles a culinary delicacy.

Demand in East Asia, in particular, has increased pressure on North American species. Back in 2008, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission estimated an average of 3,000 pounds of softshells were being exported out of the Tampa International Airport alone each week.

In 2009, in response to environmental groups and growing demand from abroad, the Florida Commission reduced the daily limit of wild-caught turtles from 20 per day per licensed harvester, to one turtle per person per day, prohibited harvesting of softshells from May through July, and banned trade in wild-caught turtles. A few other states have followed suit. Laws are definitely a step in the right direction… but not a cure-all, especially in an age when the Internet truly globalizes commerce and, it has to be said, facilitates black market trade of all manner of bush meat.

That said, softshells are carnivores, too, so surely they understand that this is an eat and be eaten world. It simply isn’t possible to be alive and not have a footprint. This is a finite planet, though, and that’s a fact often ignored by my own species, singular in its amplification of calorie consumption from need to greed. We humans ignore this reality at our own peril, and if we fail to respect the limitations of our food resources we may one day find the cupboard is bare.

Food for thought.