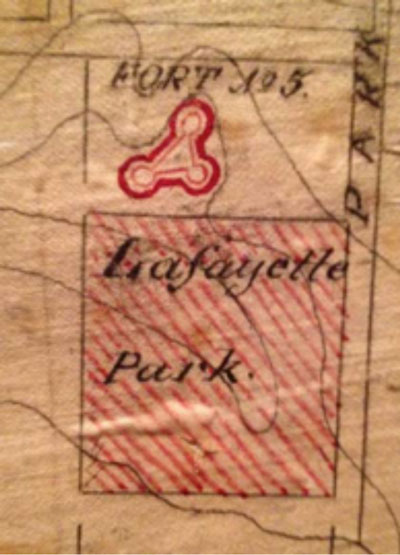

This 1860 map of Lafayette Square shows the 30-acre park just before the War Between the States, along with adjacent property owners. Montgomery Blair’s property in blue denotes sympathy to the Union cause and Edward Bredell’s in gray an alignment with the secessionist cause. (see Neighbors at War section below.) The park caretaker’s cottage is marked by a black square.

In 1861, following the secession of eight southern states, St. Louis was a gathering spot for many newly formed regiments of federal Union troops. Lafayette Park became the site of Camp Jessie, named in honor of Jessie Benton Fremont, the wife of Major-General John C. Fremont and daughter of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton.

From mid-July through August of 1861, 23 companies were encamped in Lafayette Park, about 2,300 men. The 24th Indiana, one of the first volunteer regiments, was formed in July 1861. In August, they boarded trains bound for St. Louis. A soldier recorded:

“We crossed the Mississippi on the steamer Alton City, marched two and a half miles through the city of St. Louis…and went to camp in the Lafayette Park. Here were the first tents we ever pitched, and all the boys wanted to learn how. Lafayette Park is a beautiful park. It contains many fine animals. There were many of our boys who had never seen such sites as the city of St. Louis contained. Some of them had sore eyes on account of so much sight-seeing.”

The war disrupted the sport of base ball, a game recently introduced to St. Louis in Lafayette Park, the home grounds of the Cyclone, Union and Commercial clubs. The base ball field became part of Camp Jesse. Political differences arose between team members, causing the ball clubs to disband.

Sarah Hill’s husband, a builder by trade, joined the federal army and served throughout the war as an engineer. She visited him at his camp in Lafayette Park, located in one of the city’s most fashionable neighborhoods. She wrote:

“Beautiful Lafayette Park,” recalled Hill, “with its brilliant flower beds and stretches of greensward, looking like emerald velvet, was turned into a great military camp.” She came to camp with a basket of food and enjoyed an afternoon picnic with her husband. But it seemed strange to see the park filled with tents and campfires. “On the grassy lawns that a policemen has so watchfully guarded,” she noted, “now campfires were burning and men were cooking the evening meal.” – Mrs. (Sarah Full) Hill’s Journal– Civil War Reminiscences by Mark N. Krug.

A string of 10 defensive forts lined the western edge of St. Louis at the beginning of the war. General Nathaniel Lyon selected the sites. Construction began under General John C. Fremont.

“These forts were not considerable affairs, averaging, as they did, but four guns (heavy) apiece. “ It was hoped “they would provide a good rallying point in the event of any emergency from within, as well as from without.” – Encyclopedia of the History of St. Louis, Vol. II, 1899)

The redoubts were simply named Forts Number 1, Number 2, etc. Lieutenant Julius Pitzman supervised the building of the first five forts. Fort Number 5 sat on the western edge of Lafayette Park, between Missouri and Jefferson avenues on Whittemore Place. It contained four large smoothbore guns. The fort was described in the Encyclopedia of the History of St. Louis as being quadrilateral in form, with each side about four hundred feet long. Maps depict a triangular shaped Fort No. 5.

Company G of the 60th U.S. Colored Infantry was on guard duty at Forts 5 through 10 during October through December of 1863.

Although none of the forts were ever attacked, there was a military execution at Fort Number 4, just south of Lafayette Park. On October 29, 1864, a Confederate major from General Sterling Price’s raiding force and six soldiers chosen at random from Gratiot Prison were taken to Fort Number 4 and executed by a firing squad of 56 soldiers. Three thousand people, mainly soldiers, witnessed the event. The executions were in retaliation for the execution by firing squad of a Union Army major and six soldiers at Pilot Knob, Missouri.

Lafayette Square: Neighbors at War

Bredell Family

Edward Bredell,Sr., pioneering St. Louis businessman, public school proponent and philanthropist, resided at 2110 Lafayette Avenue in the 1860s. A Confederate sympathizer, Mr. Bredell refused to take a loyalty oath in support of the Union. His wife, Angeline Perry Bredell, secretly served throughout the war as a communications courier for the Confederates via her regular wartime travels into the South.

Their son, Edward Bredell, Jr., enlisted and received a commission in the Confederate Army. He commanded a brigade of Missouri troops. Lieutenant Bredell later transferred to General Mosby’s command and was killed on November 16, 1864 at Berry’s Ferry, Virginia.

Edward Bredell Sr. travelled to Virginia to accompany his son’s remains to St. Louis. The City of St. Louis refused to issue a burial permit, forcing Mr. Bredell to temporarily bury his son’s body in the rear garden of their Lafayette Avenue home. The bereaved parents later donated a window, which still exists in the former Lafayette Park Presbyterian Church on Missouri Avenue, in memory of their son.

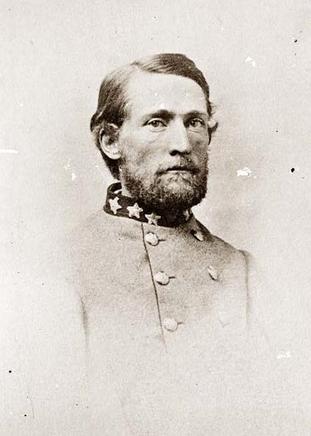

Given Campbell

Captain Given Campbell led Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s military escort in April 1865, during his escape from the Confederate capital at Richmond. He was apprehended with Davis in Georgia by Union forces, and all of his military pay was confiscated by the Union. Campbell resided at 2321 Lafayette Avenue after the war.

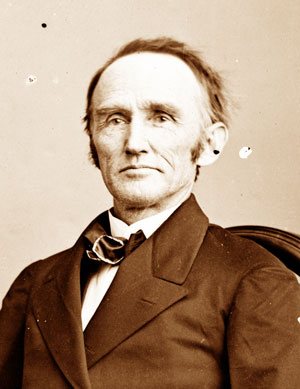

Montgomery Blair

Prior to and following the war, Montgomery Blair resided at No.1 Benton Place, on Lafayette Square land he platted in the 1850s. Blair acted as co-counselor for Dred Scott before the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark slavery case Dred Scott vs. Sanford. In 1861, President Lincoln appointed Blair Postmaster General. Blair House, the former Blair family home in Washington D.C.’s Lafayette Square is today the official state guesthouse for the President of the United States.

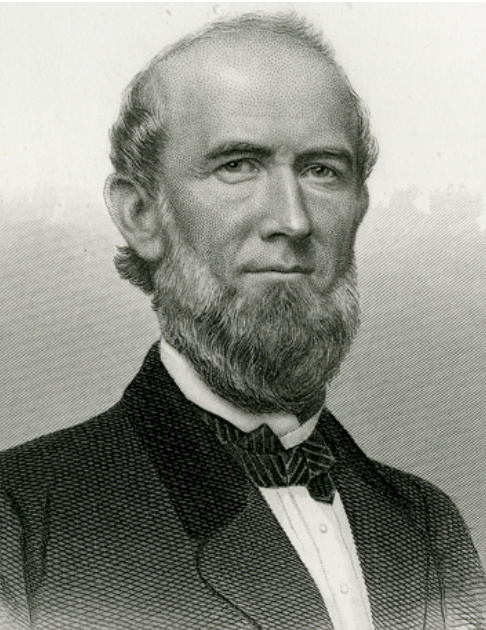

Horace Bixby

Horace Bixby resided on Mississippi Avenue across from Lafayette Park. He was a riverboat pilot and mentor to a young Sam Clemens (aka Mark Twain) in the 1850s. The Union took advantage of Bixby’s encyclopedic knowledge of the river by naming him chief pilot of the Union gunboat fleet on the Mississippi River at the outbreak of war. Bixby later achieved fame as a featured character in Mark Twain’s publication Life on the Mississippi.

James Eads

James Buchanan Eads, engineer and inventor, oversaw construction of federal ironclad gunboats at his Carondelet shipyard. He was later responsible for construction of the first bridge spanning the Mississippi at St. Louis. Homes facing Lafayette Park at 2154 and 2156 Lafayette Avenue were wedding gifts to two of Eads’ daughters. In March, 1886 his funeral cortege began its procession to his gravesite in Bellefontaine Cemetery from Lafayette Square.