BY KIERAN LINDSEY, PhD

Descendants of German immigrants are living in the city park a couple of blocks from my loft.

Nobody in this historic St. Louis neighborhood seems to mind, least of all me. In fact, this family has had an encampment there for 7 score and 10 years, so if the other residents notice them at all I suppose it’s assumed that they’ve earned squatters rights… even though the land that became Lafayette Park in 1845 has, to my knowledge, always been a commons of some sort. The park dwellers are cheerful and chipper so I find it quite delightful to run into them while my canine companion and I are out for a walk.

The founders of this settlement first arrived here from Germany in April 1870, at the invitation of one Carl Daenzer. You see, importing European songbirds to the U.S. was all the rage for a decade or so after the end of the Civil War, prior to regulation of such activities. Mr. Daenzer, a prominent German-American publisher in the city at that time, sponsored the Transatlantic voyage of a dozen Eurasian Tree Sparrows (Passer montanus, aka German sparrows) and representatives of 5 other species from his fatherland. Hoping to establish colonies in the Missouri Rhineland, shortly after their arrival the itinerant avians were released into the park.

Members of my own family made the passage from Germany to Missouri three decades earlier, in the late 1830s. My maternal grandfather, Edward Maier, was the first offshoot of his family tree to be born and raised on this side of the Atlantic. He became a journeyman printer (that’s my connection to Carl Daenzer), then married Elizabeth Wiess, who immigrated with her parents from Berne, Switzerland, to Highland, Illinois, as a toddler in the late 1890s. Edward and Elizabeth had three daughters, including my mother, Ethel, a first generation American on her mom’s side and second generation on her dad’s.

Based solely on my maternal lineage I guess I’m what you would call a Gen 2.5… but Dad’s folks left Scotland in the mid-1700s so the generational calculation is way more complicated than I’m willing to get into here. Suffice it to say I’m an All-American Mutt.

Most of Daenzer’s feathered settlers vacated the park in short order. By the summer of 1871 it was clear this range expansion experiment had fallen flat… with one exception. In no time at all the Baumsperlinge (German: tree sparrows) were feeling quite at home. Perhaps Lafayette Park’s proximity to the expanding German-American populace gave the birds a helpful boost.

Here how that worked: Thanks to rising demand from immigrants pouring in from Bavaria, Baden, Hessen, and Westphalia, local bakers and brewers were ordering wheat, rye, and barley by the horse-drawn wagon-full.

Adult tree sparrows eat a primarily grain-and-seed diet but their children (or perhaps they would prefer the German word kinder) need high-protein insects to grow. When Mütter und Väter were able to grab quick bites throughout the day by gleaning silage spillage, they had more time and energy to feed the kids and, in turn, they helped the grain-dependent businesses keep the bug population at bay.

Newcomers helping newcomers, that’s what it takes, right? Immigrants getting the job done, and then sharing their beer and pretzels!

To give you some sense of how quickly these human immigrants made their mark on St. Louis, it helps to know that approximately 18 German families called St. Louis home in 1830, and when the U.S. Census of 1880 finished its tabulations and issued a report fifty years later, over half of the city’s 350,518 residents claimed some degree of German ethnicity. Many of these individuals had risen to prominent positions of authority in the community, bought homes, and established prosperous businesses.

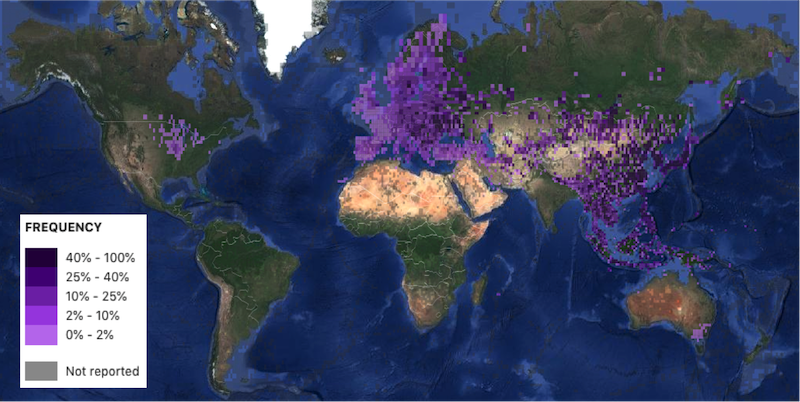

Like me, the Baumsperlinge of St. Louis have relatives in more than one country. In fact, the species has breeding populations that span most of temperate Eurasia and Southeast Asia, from Portugal to Japan, Russia to Indonesia, with some kin spending part of each year in North Africa and the Middle East. As the name implies, Tree Sparrows initially preferred to inhabit open woodlands, but eventually they began to trade tree cavities for building crevices, rural vistas for concrete canyons.

The Germans, and the German sparrows, arriving in St. Louis at that time were part of a significant exodus from Europe. The new residents quickly sorted themselves by country-of-origin into areas of town that are still referred to as Dutchtown (Germans), Dogtown (Irish), and The Hill (Italians). Both birds and bipeds adapted and assimilated to their new landscape and culture, forming multicultural friendships while also competing for jobs, space, and resources.

One such avian competitor, the house sparrow (Passer domesticus, aka English sparrow), is a close relative of the Baumsperlinge. A cohort of 100 house sparrows left England in 1851, bound for Brooklyn, New York. Subsequent expeditions over the next 25 to 30 years landed in Boston, Cleveland, and Cincinnati, and out west in San Francisco, and Salt Lake City. The eastern pioneers quickly dispersed westward, crossing over The Big Muddy to my hometown at about the same time the Tree Sparrows arrived.

In Lafayette Park the two species mingle to this day, to some extent, but that’s not common in North America. The similarities in size, shape, and coloring between these sparrows are readily apparent, yet there are recognizable differences, too. Male and female tree sparrows share a single folkloric costume and a black beauty mark on each cheek, while male and female house sparrows are easy to distinguish from one another — he usually appears to have slipped on a newly purchased suit and chapeau, while her faded outfit shows all the signs of multiple trips to the clothesline.

Truth be told, the German Sparrows haven’t done as well here as their countrymen. The progeny of those six couples who disembarked just west of the Mississippi River now inhabit an approximately 8,500 square miles of Missouri, Illinois, and Iowa, with occasional visits further north, south, east, and west. Meanwhile, house sparrows can make it anywhere… maybe that’s because they started out in New York, New York.

When I saw the Baumsperlinge in Lafayette Park the other day it set me to wondering. German-American Edward Maier, German-Swiss-American Ethel Maier Lindsey, and German-Swiss-Scottish-American me all enjoy an undisputed birthright to endemicity on this continent and in this country, even though each of us are the offspring of immigrants. So why is it that other migrant scions, including those who have been in North America for 150 generations and counting like the feathered folk living in Lafayette Park, are still officially classified by the human descendants of more recent immigrants as “non-native” and “introduced”?

I don’t have an answer to that question. All I know is that the situation seems arbitrary, more than a little unfair, and no way to treat a good neighbor.

© 2020 Next-Door Nature—no reprints without written permission from the author (I’d love for you to share my work but please ask). Thanks to these photographers for making their work available through a Creative Commons license (CCL): Wojciech Czaplejewicz, Wojciech Czaplejewicz, public domain, Biodiversity Heritage Library, State Library Victoria Collection, hedera.baltica, CW Gan, Melvin Yap, hedera.baltica, Michael Brace, hedera.baltica, Sergey Yeliseev, and 想回家的貓.