BY KIERAN LINDSEY, PhD

It isn’t easy being green. Kermit the Frog said it, so you know it has to be true.

He’s always seemed a reluctant celebrity, so my guess is that being the most famous Muppet-amphibian on the planet isn’t always a picnic. I wonder whether life would be a little less stressful if, like some of his cousins, Kermit could change from green to another color when he’d rather not be so conspicuous.

Gray treefrogs (Dryophytes versicolor) know how to be seen and when to blend into their surrounding, shifting the spectrum from bright emerald to peridot, to gold, copper, platinum, silver, and even gunmetal. Since the places they hang out — trees and shrubs in woodlands, meadows, prairies, swamps, suburbs, and cities — tend toward palettes awash with green and gray hues, these arboreal amphibians can keep their sartorial choices simple.

What looks like a costume change is actually a rather high-tech, cellular-level special effect created by chromatophores. These pigment-containing and light-reflecting cells, or groups of cells, are present in the skin of certain frogs, as well as some reptiles (including chameleons), cephalopods (such as octopi), fish, and crustaceans. Mammals and birds, on the other hand, have melanocytes, a different class of cells for coloration.

Chromatophores are classified based on their hue under white light:

-

melanophores (black/brown)

melanophores (black/brown) -

cyanophores (blue)

-

erythrophores (red)

-

xanthophores (yellow)

-

leucophores (white)

-

iridophores (reflective or iridescent)

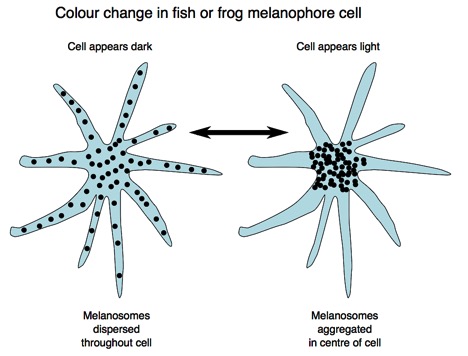

The process, known as physiological color change, can be controlled by hormones, neurons, or both. Most studies have focused primarily on melanophores because they are the darkest and, therefore, the most visible. When pigment inside the chromatophores disperses throughout cell the skin appears to darken; when pigment aggregates in cells the skin appears to lighten. Either way, you’ve got an amazing makeover, or a convincing disguise, in no time flat!

There’s even more to the gray treefrog’s ability to assume an alter-ego than meets the eye —what appears to be a single species is actually two very close relatives: Hyla versicolor, aka Eastern, although there’s a long list of pseudonyms from which to choose (there are more ways to hide than blending into the substrate); and Hyla chrysoscelis, aka Cope’s (which also has a couple of nicknames but not as many as H. versicolor).

Cope’s and Eastern are equally skilled at clinging to and climbing slick surfaces using large toe pads that secrete mucous, creating surface tension. It’s not uncommon to find one plastered against a window pane (allowing for an interesting view of their nether-regions). Both species prefer a diet of small insects, spiders, and snails. Both hibernate under leaves, bark, or rocks. Well, “hibernate” sounds a lot more cozy than the reality… which is that their bodies pretty much freeze and their lungs, heart, brain, and other organs stop working until they thaw out and reanimate in the spring. It’s a pretty nifty chemical trick, on par with being able to transform your complexion at will.

Cope’s and Eastern are equally skilled at clinging to and climbing slick surfaces using large toe pads that secrete mucous, creating surface tension. It’s not uncommon to find one plastered against a window pane (allowing for an interesting view of their nether-regions). Both species prefer a diet of small insects, spiders, and snails. Both hibernate under leaves, bark, or rocks. Well, “hibernate” sounds a lot more cozy than the reality… which is that their bodies pretty much freeze and their lungs, heart, brain, and other organs stop working until they thaw out and reanimate in the spring. It’s a pretty nifty chemical trick, on par with being able to transform your complexion at will.

Kermit has an unmistakable personal brand, but distinguishing H. versicolor from H. chrysocelis visually is just about impossible. Both Eastern and Cope’s are relatively small (1.5—2.0 in/3.5—5 cm), and the adults are often mistaken for younglings. Both wear a sweep of bright citrus-orange along the inseam of their hind legs (a signature shade is all the rage, you know). Females of both species are usually (but not always) larger, with a ladylike white throat. During the breeding season, males have a macho (make that hipster, since it resembles a beard) black, gray, or brown throat. Guys sing. Gals swoon, but don’t sing along.

The ranges of these two species overlap, but Cope’s are more widely distributed. If you find a gray treefrog in North Carolina or Georgia, you can be reasonably certain it’s a Cope’s, but if you’re in Iowa or Pennsylvania, all bets are off. The only risk-free way to know for sure is to do a DNA test — Cope’s are a diploid species, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, one from each parent (for a total of 24); Easterns are a tetraploid species, meaning they have four sets of chromosomes (for a total of 48).

Now, some frog call connoisseurs claim they can detect variations in breeding calls, and that Cope’s treefrogs have a faster and slightly higher-pitched trill than Easterns. But the call rates of both species change with ambient temperature… so color me skeptical.

Postscript: What kind of frog is Kermit? While I’ve never found a definitive answer to this question, I always assumed that because he was created/discovered by Jim Henson, he was probably Hyla muppetalis or Rana hensonii… something like that. However, in 2015 Brian Kubicki of the Costa Rican Amphibian Research Center discovered a frog who, if not the same species, must at least be a first cousin, or possibly Kermit’s doppleganger.